Tip No. 8: “There is nothing worse than a sharp image of a fuzzy concept.”

— Ansel Adams, noted American photographer, 1902-1994

Tip No. 219: “Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and

looks like work.”

— Thomas A. Edison, American inventor and businessman, 1847-1931

Improve Communications And

Watch yourself Soar

Developing the ability to speak with power and passion takes time and effort to master, but it will pay off in big dividends.

Review strategies to help you improve contacts with customers, colleagues and family. Today we’ll look at the Passive, Harmonious Watcher and the Analytical, Cautious Thinker. Tomorrow we’ll discuss Magic Words and Power Phrases.

During your next meeting, try to recognize your associates temperament style and use as many of these words as feasible.

Think Service

Persons with the Passive, Harmonious Watcher temperament style are service oriented. They ask “how” questions.

Watchers value appreciation and fear conflict. When presenting to this buying style use these words: support, service, family, harmony, dependable, caring, cooperation and helpful.

Also words like easy, sincere, love, kindness, concern, considerate, gentle and relationship.

Quality First

The Analytical, Cautious Thinker style of communicators are quality oriented. They ask “why” questions.

Thinkers value accuracy and fear being viewed as incompetent. When presenting to this buying style use these words: safe, scientific, proven, value, learn and guaranteed.

Also try using words like save, bargain, economical, quality, logical, reliable, accurate, perfect, security, precise and efficient.

–Source: John Boe presents a wide variety of motivational and sales-oriented keynote speeches and seminar programs for sales meetings and conventions. John is a nationally recognized sales trainer and business motivational speaker.

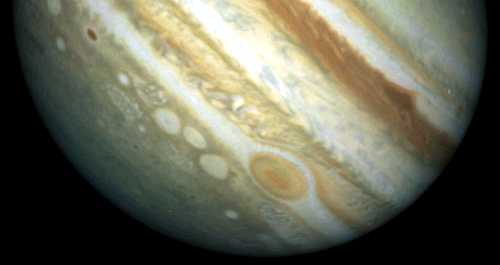

Venus is the second planet from the Sun and the sixth largest. Venus’ orbit is the most nearly circular of that of any planet, with an eccentricity of less than 1%.

orbit: 108,200,000 km (0.72 AU) from Sun

diameter: 12,103.6 km

mass: 4.869e24 kg

Venus (Greek: Aphrodite; Babylonian: Ishtar) is the goddess of love and beauty. The planet is so named probably because it is the brightest of the planets known to the ancients. (With a few exceptions, the surface features on Venus are named for female figures.)

Venus has been known since prehistoric times. It is the brightest object in the sky except for the Sun and the Moon. Like Mercury, it was popularly thought to be two separate bodies: Eosphorus as the morning star and Hesperus as the evening star, but the Greek astronomers knew better.

Since Venus is an inferior planet, it shows phases when viewed with a telescope from the perspective of Earth. Galileo’s observation of this phenomenon was important evidence in favor of Copernicus’s heliocentric theory of the solar system.

The first spacecraft to visit Venus was Mariner 2 in 1962. It was subsequently visited by many others (more than 20 in all so far), including Pioneer Venus and the Soviet Venera 7 the first spacecraft to land on another planet, and Venera 9 which returned the first photographs of the surface (left). Most recently, the orbiting US spacecraft Magellan produced detailed maps of Venus’ surface using radar (above).

The first spacecraft to visit Venus was Mariner 2 in 1962. It was subsequently visited by many others (more than 20 in all so far), including Pioneer Venus and the Soviet Venera 7 the first spacecraft to land on another planet, and Venera 9 which returned the first photographs of the surface (left). Most recently, the orbiting US spacecraft Magellan produced detailed maps of Venus’ surface using radar (above).

Venus’ rotation is somewhat unusual in that it is both very slow (243 Earth days per Venus day, slightly longer than Venus’ year) and retrograde. In addition, the periods of Venus’ rotation and of its orbit are synchronized such that it always presents the same face toward Earth when the two planets are at their closest approach. Whether this is a resonance effect or merely a coincidence is not known.

Venus is sometimes regarded as Earth’s sister planet. In some ways they are very similar:

— Venus is only slightly smaller than Earth (95% of Earth’s diameter, 80% of Earth’s mass).

— Both have few craters indicating relatively young surfaces.

— Their densities and chemical compositions are similar.

Because of these similarities, it was thought that below its dense clouds Venus might be very Earthlike and might even have life. But, unfortunately, more detailed study of Venus reveals that in many important ways it is radically different from Earth.

The pressure of Venus’ atmosphere at the surface is 90 atmospheres (about the same as the pressure at a depth of 1 km in Earth’s oceans). It is composed mostly of carbon dioxide. There are several layers of clouds many kilometers thick composed of sulfuric acid. These clouds completely obscure our view of the surface. This dense atmosphere produces a run-away greenhouse effect that raises Venus’ surface temperature by about 400 degrees to over 740 K (hot enough to melt lead). Venus’ surface is actually hotter than Mercury’s despite being nearly twice as far from the Sun.

There are strong (350 kph) winds at the cloud tops but winds at the surface are very slow, no more than a few kilometers per hour.

There are strong (350 kph) winds at the cloud tops but winds at the surface are very slow, no more than a few kilometers per hour.

Venus probably once had large amounts of water like Earth but it all boiled away. Venus is now quite dry. Earth would have suffered the same fate had it been just a little closer to the Sun. We may learn a lot about Earth by learning why the basically similar Venus turned out so differently.

Most of Venus’ surface consists of gently rolling plains with little relief. There are also several broad depressions: Atalanta Planitia, Guinevere Planitia, Lavinia Planitia. There two large highland areas: Ishtar Terra in the northern hemisphere (about the size of Australia) and Aphrodite Terra along the equator (about the size of South America). The interior of Ishtar consists mainly of a high plateau, Lakshmi Planum, which is surrounded by the highest mountains on Venus including the enormous Maxwell Montes.

Data from Magellan’s imaging radar shows that much of the surface of Venus is covered by lava flows. There are several large shield volcanoes (similar to Hawaii or Olympus Mons) such as Sif Mons (right). Recently announced findings indicate that Venus is still volcanically active, but only in a few hot spots; for the most part it has been geologically rather quiet for the past few hundred million years.

Data from Magellan’s imaging radar shows that much of the surface of Venus is covered by lava flows. There are several large shield volcanoes (similar to Hawaii or Olympus Mons) such as Sif Mons (right). Recently announced findings indicate that Venus is still volcanically active, but only in a few hot spots; for the most part it has been geologically rather quiet for the past few hundred million years.

There are no small craters on Venus. It seems that small meteoroids burn up in Venus’ dense atmosphere before reaching the surface. Craters on Venus seem to come in bunches indicating that large meteoroids that do reach the surface usually break up in the atmosphere.

The oldest terrains on Venus seem to be about 800 million years old. Extensive volcanism at that time wiped out the earlier surface including any large craters from early in Venus’ history.

Magellan’s images show a wide variety of interesting and unique features including pancake volcanoes (left) which seem to be eruptions of very thick lava and coronae (right) which seem to be collapsed domes over large magma chambers.

Magellan’s images show a wide variety of interesting and unique features including pancake volcanoes (left) which seem to be eruptions of very thick lava and coronae (right) which seem to be collapsed domes over large magma chambers.

The interior of Venus is probably very similar to that of Earth: an iron core about 3000 km in radius, a molten rocky mantle comprising the majority of the planet. Recent results from the Magellan gravity data indicate that Venus’ crust is stronger and thicker than had previously been assumed. Like Earth, convection in the mantle produces stress on the surface which is relieved in many relatively small regions instead of being concentrated at plate boundaries as is the case on Earth.

Venus has no magnetic field, perhaps because of its slow rotation.

Venus has no satellites, and thereby hangs a tale.

Venus is usually visible with the unaided eye. Sometimes (inaccurately) referred to as the “morning star” or the “evening star”, it is by far the brightest “star” in the sky. There are several Web sites that show the current position of Venus (and the other planets) in the sky. More detailed and customized charts can be created with a planetarium program such as Starry Night.

Open Issues

- There is some evidence of spreading and folding on Venus’ surface and of recent volcanic flows. But there is no evidence of plate tectonics as seen on Earth. Is this a result of the higher surface temperature?

- The greenhouse effect is much stronger on Venus than Earth because of Venus’ dense carbon dioxide atmosphere. But why did Venus evolve so differently from Earth?

Venus, playing one day with her boy Cupid, wounded her bosom with one of his arrows. She pushed him away, but the wound was deeper than she thought. Before it healed she beheld Adonis, and was captivated with him. She no longer took any interest in her favourite resorts- Paphos, and Cnidos, and Amathos, rich in metals. She absented herself even from heaven, for Adonis was dearer to her than heaven. Him she followed and bore him company. She who used to love to recline in the shade, with no care but to cultivate her charms, now rambles through the woods and over the hills, dressed like the huntress Diana; and calls her dogs, and chases hares and stags, or other game that it is safe to hunt, but keeps clear of the wolves and bears, reeking with the slaughter of the herd. She charged Adonis, too, to beware of such dangerous animals. “Be brave towards the timid,” said she; “courage against the courageous is not safe. Beware how you expose yourself to danger and put my happiness to risk. Attack not the beasts that Nature has armed with weapons. I do not value your glory so high as to consent to purchase it by such exposure. Your youth, and the beauty that charms Venus, will not touch the hearts of lions and bristly boars. Think of their terrible claws and prodigious strength! I hate the whole race of them. Do you ask me why?” Then she told him the story of Atalanta and Hippomenes, who were changed into lions for their ingratitude to her.

Having given him this warning, she mounted her chariot drawn by swans, and drove away through the air. But Adonis was too noble to heed such counsels. The dogs had roused a wild boar from his lair, and the youth threw his spear and wounded the animal with sidelong stroke. The beast drew out the weapon with his jaws, and rushed after Adonis, who turned and ran; but the boar overtook him, and buried his tusks in his side, and stretched him dying upon the plain.

Venus, in her swan-drawn chariot, had not yet reached Cyprus, when she heard coming up through mid-air the groans of her beloved, and turned her white-winged coursers back to earth. As she drew near and saw from on high his lifeless body bathed in blood, she alighted and, bending over it, beat her breast and tore her hair. Reproaching the Fates, she said, “Yet theirs shall be but a partial triumph; memorials of my grief shall endure, and the spectacle of your death, my Adonis, and of my lamentation shall be annually renewed. Your blood shall be changed into a flower; that consolation none can envy me.” Thus speaking, she sprinkled nectar on the blood; and as they mingled, bubbles rose as in a pool on which raindrops fall, and in an hour’s time there sprang up a flower of bloody hue like that of the pomegranate. But it is short-lived. It is said the wind blows the blossoms open, and afterwards blows the petals away; so it is called Anemone, or Wind Flower, from the cause which assists equally in its production and its decay.

Milton alludes to the story of Venus and Adonis in his “Comus”:

“Beds of hyacinth and roses

Where young Adonis oft reposes,

Waxing well of his deep wound

In slumber soft, and on the ground

Sadly sits th’ Assyrian queen;” etc.

APOLLO AND HYACINTHUS

Apollo was passionately fond of a youth named Hyacinthus. He. accompanied him in his sports, carried the nets when he went fishing, led the dogs when he went to hunt, followed him in his excursions in the mountains, and neglected for him his lyre and his arrows. One day they played a game of quoits together, and Apollo, heaving aloft the discus, with strength mingled with skill, sent it high and far. Hyacinthus watched it as it flew, and excited with the sport ran forward to seize it, eager to make his throw, when the quoit bounded from the earth and struck him in the forehead. He fainted and fell. The god, as pale as himself, raised him and tried all his art to stanch the wound and retain the flitting life, but all in vain; the hurt was past the power of medicine. As when one has broken the stem of a lily in the garden it hangs its head and turns its flowers to the earth, so the head of the dying boy, as if too heavy for his neck, fell over on his shoulder. “Thou diest, Hyacinth,” so spoke Phoebus, “robbed of thy youth by me. Thine is the suffering, mine the crime. Would that I could die for thee! But since that may not be, thou shalt live with me in memory and in song. My lyre shall celebrate thee, my song shall tell thy fate, and thou shalt become a flower inscribed with my regrets.” While Apollo spoke, behold the blood which had flowed on the ground and stained the herbage ceased to be blood; but a flower of hue more beautiful than the Tyrian sprang up, resembling the lily, if it were not that this is purple and that silvery white.* And this was not enough for Phoebus; but to confer still greater honour, he marked the petals with his sorrow, and inscribed “Ah! ah!” upon them, as we see to this day. The flower bears the name of Hyacinthus, and with every returning spring revives the memory of his fate.

* It is evidently not our modern hyacinth that is here described. It is perhaps some species of iris, or perhaps of larkspur or pansy.

It was said that Zephyrus (the West wind), who was also fond of Hyacinthus and jealous of his preference of Apollo, blew the quoit out of its course to make it strike Hyacinthus. Keats alludes to this in his “Endymion,” where he describes the lookers-on at the game of quoits:

“Or they might watch the quoit-pitchers, intent

On either side, pitying the sad death

Of Hyacinthus, when the cruel breath

Of Zephyr slew him; Zephyr penitent,

Who now ere Phoebus mounts the firmament,

Fondles the flower amid the sobbing rain.”

An allusion to Hyacinthus will also be recognized in Milton’s “Lycidas”:

“Like to that sanguine flower inscribed with woe.”

CEYX AND HALCYONE

or

THE HALCYON BIRDS

CEYX was king of Thessaly, where he reigned in peace, without violence or wrong. He was son of Hesperus, the Day-star, and the glow of his beauty reminded one of his father. Halcyone, the daughter of AEolus, was his wife, and devotedly attached to him. Now Ceyx was in deep affliction for the loss of his brother, and direful prodigies following his brother’s death made him feel as if the gods were hostile to him. He thought best, therefore, to make a voyage to Carlos in Ionia, to consult the oracle of Apollo. But as soon as he disclosed his intention to his wife Halcyone, a shudder ran through her frame, and her face grew deadly pale. “What fault of mine, dearest husband, has turned your affection from me? Where is that love of me that used to be uppermost in your thoughts? Have you learned to feel easy in the absence of Halcyone? Would you rather have me away;” She also endeavoured to discourage him, by describing the violence of the winds, which she had known familiarly when she lived at home in her father’s house,- AEolus being the god of the winds, and having as much as he could do to restrain them. “They rush together,” said she, “with such fury that fire flashes from the conflict. But if you must go,” she added, “dear husband, let me go with you, otherwise I shall suffer not only the real evils which you must encounter, but those also which my fears suggest.”

These words weighed heavily on the mind of King Ceyx, and it was no less his own wish than hers to take her with him, but he could not bear to expose her to the dangers of the sea. He answered. therefore, consoling her as well as he could, and finished with these words: “I promise, by the rays of my father the Day-star, that if fate permits I will return before the moon shall have twice rounded her orb.” When he had thus spoken, he ordered the vessel to be drawn out of the shiphouse, and the oars and sails to be put aboard When Halcyone saw these preparations she shuddered, as if with a presentiment of evil. With tears and sobs she said farewell, and then fell senseless to the ground.

Ceyx would still have lingered, but now the young men grasped their oars and pulled vigorously through the waves, with long and measured strokes. Halcyone raised her streaming eyes, and saw her husband standing on the deck, waving his hand to her. She answered his signal till the vessel had receded so far that she could no longer distinguish his form from the rest. When the vessel itself could no more be seen, she strained her eyes to catch the last glimmer of the sail, till that too disappeared. Then, retiring to her chamber, she threw herself on her solitary couch.

Meanwhile they glide out of the harbour, and the breeze plays among the ropes. The seamen draw in their oars, and hoist their sails. When half or less of their course was passed, as night drew on, the sea began to whiten with swelling waves, and the east wind to blow a gale. The master gave the word to take in sail, but the storm forbade obedience, for such is the roar of the winds and waves his orders are unheard. The men, of their own accord, busy themselves to secure the oars, to strengthen the ship, to reef the sail. While they thus do what to each one seems best, the storm increases. The shouting of the men, the rattling of the shrouds, and the dashing of the waves, mingle with the roar of the thunder. The swelling sea seems lifted up to the heavens, to scatter its foam among the clouds; then sinking away to the bottom assumes the colour of the shoal-a Stygian blackness.

The vessel shares all these changes. It seems like a wild beast that rushes on the spears of the hunters. Rain falls in torrents, as if the skies were coming down to unite with the sea. When the lightning ceases for a moment, the night seems to add its own darkness to that of the storm; then comes the flash, rending the darkness asunder, and lighting up all with a glare. Skill fails, courage sinks, and death seems to come on every wave. The men are stupefied with terror. The thought of parents, and kindred, and pledges left at home, comes over their minds. Ceyx thinks of Halcyone. No name but hers is on his lips, and while he yearns for her, he yet rejoices in her absence. Presently the mast is shattered by a stroke of lightning, the rudder broken, and the triumphant surge curling over looks down upon the wreck, then falls, and crushes it to fragments. Some of the seamen, stunned by the stroke, sink, and rise no more; others cling to fragments of the wreck. Ceyx, with the hand that used to grasp the sceptre, holds fast to a plank, calling for help,- alas, in vain,-upon his father and his father-in-law. But oftenest on his lips was the name of Halcyone. To her his thoughts cling. He prays that the waves may bear his body to her sight, and that it may receive burial at her hands. At length the waters overwhelm him, and he sinks. The Day-star looked dim that night. Since it could not leave the heavens, it shrouded its face with clouds.

In the meanwhile Halcyone, ignorant of all these horrors, counted the days till her husband’s promised return. Now she gets ready the garments which he shall put on, and now what she shall wear when he arrives. To all the gods she offers frequent incense, but more than all to Juno. For her husband, who was no more, she prayed incessantly: that be might be safe; that he might come home; that he might not, in his absence, see any one that he would love better than her. But of all these prayers, the last was the only one destined to be granted. The goddess, at length, could not bear any longer to be pleaded with for one already dead, and to have hands raised to her altars that ought rather to be offering funeral rites. So, calling Iris, she said, “Iris, my faithful messenger, go to the drowsy dwelling of Somnus, and tell him to send a vision to Halcyone in the form of Ceyx, to make known to her the event.”

Iris puts on her robe of many colours, and tinging the sky with her bow, seeks the palace of the King of Sleep. Near the Cimmerian country, a mountain cave is the abode of the dull god Somnus. Here Phoebus dares not come, either rising, at midday, or setting. Clouds and shadows are exhaled from the ground, and the light glimmers faintly. The bird of dawning, with crested head, never there calls aloud to Aurora, nor watchful dog, nor more sagacious goose disturbs the silence. No wild beast, nor cattle, nor branch moved with the wind, nor sound of human conversation, breaks the stillness. Silence reigns there; but from the bottom of the rock the River Lethe flows, and by its murmur invites to sleep. Poppies grow abundantly before the door of the cave, and other herbs, from whose juices Night collects slumbers, which she scatters over the darkened earth. There is no gate to the mansion, to creak on its hinges, nor any watchman; but in the midst a couch of black ebony, adorned with black plumes and black curtains. There the god reclines, his limbs relaxed with sleep. Around him lie dreams, resembling all various forms, as many as the harvest bears stalks, or the forest leaves, or the seashore sand grains.

As soon as the goddess entered and brushed away the dreams that hovered around her, her brightness lit up all the cave. The god, scarce opening his eyes, and ever and anon dropping his beard upon his breast, at last shook himself free from himself, leaning on his arm, inquired her errand,- for he knew who she was. She answered, “Somnus, gentlest of the gods, tranquillizer of minds and soother of care-worn hearts, Juno sends you her commands that you despatch a dream to Halcyone, in the city of Trachine, representing her lost husband and all the events of the wreck.”

Having delivered her message, Iris hasted away, for she could not longer endure the stagnant air, and as she felt drowsiness creep. ing over her, she made her escape, and returned by her bow the way she came. Then Somnus called one of his numerous sons,- Morpheus,- the most expert in counterfeiting forms, and in imitating the walk, the countenance, and mode of speaking, even the clothes and attitudes most characteristic of each. But he only imitates men, leaving it to another to personate birds, beasts, and serpents. Him they call Icelos; and Phantasos is a third, who turns himself into rocks, waters, woods, and other things without life. These wait upon kings and great personages in their sleeping hours, while others move among the common people. Somnus chose, from all the brothers, Morpheus, to perform the command of Iris; then laid his head on his pillow and yielded himself to grateful repose.

Morpheus flew, making no noise with his wings, and soon came to the Haemonian city, where, laying aside his wings, he assumed the form of Ceyx. Under that form, but pale like a dead man, naked, he stood before the couch of the wretched wife. His beard seemed soaked with water, and water trickled from his drowned locks. Leaning over the bed, tears streaming from his eyes, he said, “Do you recognize your Ceyx, unhappy wife, or has death too much changed my visage? Behold me, know me, your husband’s shade, instead of himself. Your prayers, Halcyone, availed me nothing. I am dead. No more deceive yourself with vain hopes of my return. The stormy winds sunk my ship in the AEgean Sea, waves filled my mouth while it called aloud on you. No uncertain messenger tells you this, no vague rumour brings it to your ears. I come in person, a shipwrecked man, to tell you my fate. Arise! give me tears, give me lamentations, let me not go down to Tartarus unwept.” To these words Morpheus added the voice, which seemed to be that of her husband; he seemed to pour forth genuine tears; his hands had the gestures of Ceyx.

Halcyone, weeping, groaned, and stretched out her arms in her sleep, striving to embrace his body, but grasping only the air. “Stay!” she cried; “whither do you fly? let us go together.” Her own voice awakened her. Starting up, she gazed eagerly around, to see if he was still present, for the servants, alarmed by her cries, had brought a light. When she found him not, she smote her breast and rent her garments. She cares not to unbind her hair, but tears it wildly. Her nurse asks what is the cause of her grief. “Halcyone is no more,” she answers, “she perished with her Ceyx. Utter not words of comfort, he is shipwrecked and dead. I have seen him, I have recognized him. I stretched out my hands to seize him and detain him. His shade vanished, but it was the true shade of my husband. Not with the accustomed features, not with the beauty that was his, but pale, naked, and with his hair wet with sea water, he appeared to wretched me. Here, in this very spot, the sad vision stood,”- and she looked to find the mark of his footsteps. “This it was, this that my presaging mind foreboded, when I implored him not to leave me, to trust himself to the waves. Oh, how I wish, since thou wouldst go, thou hadst taken me with thee! It would have been far better. Then I should have had no remnant of life to spend without thee, nor a separate death to die. If I could bear to live and struggle to endure, I should be more cruel to myself than the sea has been to me. But I will not struggle, I will not be separated from thee, unhappy husband. This time, at least, I will keep thee company. In death, if one tomb may not include us, one epitaph shall; if I may not lay my ashes with thine, my name, at least, shall not be separated.” Her grief forbade more words, and these were broken with tears and sobs.

It was now morning. She went to the seashore, and sought the spot where she last saw him, on his departure. “While he lingered here, and cast off his tacklings, he gave me his last kiss.” While she reviews every object, and strives to recall every incident, looking out over the sea, she descries an indistinct object floating in the water. At first she was in doubt what it was, but by degrees the waves bore it nearer, and it was plainly the body of a man. Though unknowing of whom, yet, as it was of some shipwrecked one, she was deeply moved, and gave it her tears, saying, “Alas! unhappy one, and unhappy, if such there be, thy wife!” Borne by the waves, it came nearer. As she more and more nearly views it, she trembles more and more. Now, now it approaches the shore. Now marks that she recognizes appear. it is her husband! Stretching out her trembling hands towards it, she exclaims, “O dearest husband, is it thus you return to me?”

There was built out from the shore a mole, constructed to break the assaults of the sea, and stem its violent ingress. She leaped upon this barrier and (it was wonderful she could do so) she flew, and striking the air with wings produced on the instant, skimmed along the surface of the water, an unhappy bird. As she flew, her throat poured forth sounds full of grief, and like the voice of one lamenting. When she touched the mute and bloodless body, she enfolded its beloved limbs with her new-formed wings, and tried to give kisses with her horny beak. Whether Ceyx felt it, or whether it was only the action of the waves, those who looked on doubted, but the body seemed to raise its head. But indeed he did feel it, and by the pitying gods both of them were changed into birds. They mate and have their young ones. For seven placid days, in winter time, Halcyone broods over her nest, which floats upon the sea. Then the way is safe to seamen. AEolus guards the winds and keeps them from disturbing the deep. The sea is given up, for the time, to his grandchildren.

The following lines from Byron’s “Bride of Abydos” might seem borrowed from the concluding part of this description, if it were not stated that the author derived the suggestion from observing the motion of a floating corpse:

“As shaken on his restless pillow,

His head heaves with the heaving billow;

That hand, whose motion is not life,

Yet feebly seems to menace strife,

Flung by the tossing tide on high,

Then levelled with the wave…”

Milton, in his “Hymn on the Nativity,” thus alludes to the fable of the Halcyon:

“But peaceful was the night

Wherein the Prince of light

His reign of peace upon the earth began;

The winds with wonder whist

Smoothly the waters kist

Whispering new joys to the mild ocean,

Who now hath quite forgot to rave

While birds of calm sit brooding on the charmed wave.”

Keats also, in “Endymion,” says:

“O magic sleep! O comfortable bird

That broodest o’er the troubled sea of the mind

Till it is hushed and smooth.”

VERTUMNUS AND POMONA

THE Hamadryads were Wood-nymphs. Pomona was of this class. and no one excelled her in love of the garden and the culture of fruit. She cared not for forests and rivers, but loved the cultivated country, and trees that bear delicious apples. Her right hand bore for its weapon not a javelin, but a pruning-knife. Armed with this, she busied herself at one time to repress the too luxuriant growths: and curtail the branches that straggled out of place; at another, to split the twig and insert therein a graft, making the branch adopt a nursling not its own. She took care, too, that her favourites should not suffer from drought, and led streams of water by them, that the thirsty roots might drink. This occupation was her pursuit, her passion; and she was free from that which Venus inspires. She was not without fear of the country people, and kept her orchard locked, and allowed not men to enter. The Fauns and Satyrs would have given all they possessed to win her, and so would old Sylvanus, who looks young for his years, and Pan, who wears a garland of pine leaves around his head. But Vertumnus loved her best of all; yet he sped no better than the rest. O how often, in the disguise of a reaper, did he bring her corn in a basket, and looked the very image of a reaper! With a hay band tied round him, one would think he had just come from turning over the grass. Sometimes he would have an ox-goad in his hand, and you would have said he had just unyoked his weary oxen. Now he bore a pruning-hook, and personated a vine-dresser; and again, with a ladder on his shoulder, he seemed as if he was going to gather apples. Sometimes he trudged along as a discharged soldier, and again he bore a fishing-rod, as if going to fish. In this way he gained admission to her again and again, and fed his passion with the sight of her.

One day he came in the guise of an old woman, her grey hair surmounted with a cap, and a staff in her hand. She entered the garden and admired the fruit. “It does you credit, my dear,” she said, and kissed her not exactly with an old woman’s kiss. She sat down on a bank, and looked up at the branches laden with fruit which hung over her. Opposite was an elm entwined with a vine loaded with swelling grapes. She praised the tree and its associated vine, equally. “But,” said she, “if the tree stood alone, and had no vine clinging to it, it would have nothing to attract or offer us but its useless leaves. And equally the vine, if it were not twined round the elm, would lie prostrate on the ground. Why will you not take a lesson from the tree and the vine, and consent to unite yourself with some one? I wish you would. Helen herself had not more numerous suitors, nor Penelope, the wife of shrewd Ulysses. Even while you spurn them, they court you,- rural deities and others of every kind that frequent these mountains. But if you are prudent and want to make a good alliance, and will let an old woman advise you,- who loves you better than you have any idea of,- dismiss all the rest and accept Vertumnus, on my recommendation. I know him as well as he knows himself. He is not a wandering deity, but belongs to these mountains. Nor is he like too many of the lovers nowadays, who love any one they happen to see; he loves you, and you only. Add to this, he is young and handsome, and has the art of assuming any shape he pleases, and can make himself just what you command him. Moreover, he loves the same things that you do, delights in gardening, and handles your apples with admiration. But now he cares nothing for fruits nor flowers, nor anything else, but only yourself. Take pity on him, and fancy him speaking now with my mouth. Remember that the gods punish cruelty, and that Venus hates a hard heart, and will visit such offences sooner or later. To prove this, let me tell you a story, which is well known in Cyprus to be a fact; and I hope it will have the effect to make you more merciful.

“Iphis was a young man of humble parentage, who saw and loved Anaxarete, a noble lady of the ancient family of Teucer. He struggled long with his passion, but when he found he could not subdue it, he came a suppliant to her mansion. First he told his passion to her nurse, and begged her as she loved her foster-child to favour his suit. And then he tried to win her domestics to his side. Sometimes he committed his vows to written tablets, and often hung at her door garlands which he had moistened with his tears. He stretched himself on her threshold, and uttered his complaints to the cruel bolts and bars. She was deafer than the surges which rise in the November gale; harder than steel from the German forges, or a rock that still clings to its native cliff. She mocked and laughed at him, adding cruel words to her ungentle treatment, and gave not the slightest gleam of hope.

“Iphis could not any longer endure the torments of hopeless love, and, standing before her doors, he spake these last words: ‘Anaxarete, you have conquered, and shall no longer have to bear my importunities. Enjoy your triumph! Sing songs of joy, and bind your forehead with laurel,- you have conquered! I die; stony heart, rejoice! This at least I can do to gratify you, and force you to praise me; and thus shall I prove that the love of you left me but with life. Nor will I leave it to rumour to tell you of my death. I will come myself, and you shall see me die, and feast your eyes on the spectacle. Yet, O ye Gods, who look down on mortal woes, observe my fate! I ask but this: let me be remembered in coming ages, and add those years to my fame which you have reft from my life.’ Thus he said, and, turning his pale face and weeping eyes towards her mansion, he fastened a rope to the gate-post, on which he had often hung garlands, and putting his head into the noose, he murmured, ‘This garland at least will please you, cruel girl!’ and falling hung suspended with his neck broken. As he fell he struck against the gate, and the sound was as the sound of a groan. The servants opened the door and found him dead, and with exclamations of pity raised him and carried him home to his mother, for his father was not living. She received the dead body of her son, and folded the cold form to her bosom, while she poured forth the sad words which bereaved mothers utter. The mournful funeral passed through the town, and the pale corpse was borne on a bier to the place of the funeral pile. By chance the home of Anaxarete was on the street where the procession passed, and the lamentations of the mourners met the ears of her whom the avenging deity had already marked for punishment.

“‘Let us see this sad procession,’ said she, and mounted to a turret, whence through an open window she looked upon the funeral. Scarce had her eyes rested upon the form of Iphis stretched on the bier, when they began to stiffen, and the warm blood in her body to become cold. Endeavouring to step back, she found she could not move her feet; trying to turn away her face, she tried in vain; and by degrees all her limbs became stony like her heart. That you may not doubt the fact, the statue still remains, and stands in the temple of Venus at Salamis, in the exact form of the lady. Now think of these things, my dear, and lay aside your scorn and your delays, and accept a lover. So may neither the vernal frosts blight your young fruits, nor furious winds scatter your blossoms!”

When Vertumnus had spoken thus, be dropped the disguise of an old woman, and stood before her in his proper person, as a comely youth. It appeared to her like the sun bursting through a cloud. He would have renewed his entreaties, but there was no need; his arguments and the sight of his true form prevailed, and the Nymph no longer resisted, but owned a mutual flame.

Pomona was the especial patroness of the Apple-orchard, and as such she was invoked by Phillips, the author of a poem on Cider, in blank verse. Thomson in the “Seasons” alludes to him:

“Phillips, Pomona’s bard, the second thou

Who nobly durst, in rhyme-unfettered verse,

With British freedom, sing the British song.”

But Pomona was also regarded as presiding over other fruits, and as such is invoked by Thomson:

“Bear me, Pomona, to thy citron groves,

To where the lemon and the piercing lime,

With the deep orange, glowing through the green,

Their lighter glories blend. Lay me reclined

Beneath the spreading tamarind, that shakes,

Fanned by the breeze, its fever-cooling fruit.”